Who was Ueli Steck? The “Swiss Machine” mountaineer who broke records on the world’s most iconic peaks

Ueli Steck’s warm character, insatiable drive and astonishing climbs made him one of the greatest climbers and mountaineers of the modern era

On April 30, 2017, the sudden death of 40-year-old climbing superstar Ueli Steck sent shockwaves through the adventure world. He’d suffered a fall while climbing Nuptse as part of his bid to pull off a hugely accomplished traverse of Everest and Lhotse. Dubbed “the Swiss Machine”, Steck was undoubtedly one of the greatest mountaineers in the world at the time, renowned for his speed and ability on the Earth’s most fearsome lines.

Steck disliked the Machine nickname, given to him because of his incredible efficiency and the focus he brought to preparing for and carrying out his climbs. However, the nickname also suggests a coldness that, according to those that knew him, couldn’t be further from the truth. Steck was a friendly, thoughtful and warm character, with vulnerabilities just like the rest of us.

So, just who was Ueli Steck really? We asked one of our mountaineering experts to delve into his life and put his many achievements into context.

Early life

Steck was born on 4 October 1976 in Langnau in the Emmental, the Swiss valley where the iconic cheese comes from. His family were sporty – one of his brothers would go on to play professional ice hockey – though it was through a family family friend, Fritz Morgenthaler, that he was introduced to the world of climbing. Morgenthaler took Steck onto the limestone of the Schrattenfluh, a 2,092-meter mountain in the Upper Emmental. For Steck, it would spark the passion of a lifetime.

By his mid-teens, climbing had taken over his life and, by 16, he was rock climbing with the best. He gained wider renown at the age of 18 when he conquered the Eiger’s fearsome North Face for the first time, enduring a soaking wet overnight bivouac with his climbing partner. In the same year, he succeeded on the classic Bonatti Pillar on the Aiguille du Dru in the Mont Blanc massif – a demanding test piece for elite alpinists. It was clear to onlookers that Steck was a prodigious talent.

Meet the expert

Alex is a keen mountaineer and former President of the London Mountaineering Club. He’s happiest in either Scotland’s winter mountains or taking on Alpine 4,000ers on the European continent. He follows the world of elite mountaineering with great interest.

The Eiger

Steck was perhaps best known for the speed of his climbs, something that he’d garner both praise and attract criticism for. His argument was that speed equalled safety, that the less time he spent in dangerous positions, the less chance there’d be of getting caught out by something like rockfall or an avalanche. Steck was also of the mindset that going fast on known routes was good preparation for successful climbs on higher mountains in the Greater Ranges.

Among his most celebrated ascents are his speed records on the Eiger’s Nordwand, one of the world’s greatest north faces. This dark 1,800-meter wall of rock and ice has been a testing ground for alpinists for almost 100 years and has earned the nickname the Mordwand – the murder wall. Steck has broken the speed record on the face three times, the first two times in 2007 and 2008, and then again in 2015 after fellow Swiss mountaineer Dani Arnold had taken the record. His 2015 effort came after he’d already climbed the face on three occasions in the immediate lead up, once aside fellow speed merchant Kilian Jornet. The record he set on the Heckmair Route still stands to this day, at 2 hours, 22 minutes and 50 seconds.

Advnture Newsletter

All the latest inspiration, tips and guides to help you plan your next Advnture!

Success and tragedy in the Greater Ranges

With the Alps as his stomping ground and his scientific approach to training and conditioning, the mountain world was Steck’s oyster. As is often the case among the alpine elite, his trips to the Greater Ranges delivered a mixture success and tragedy.

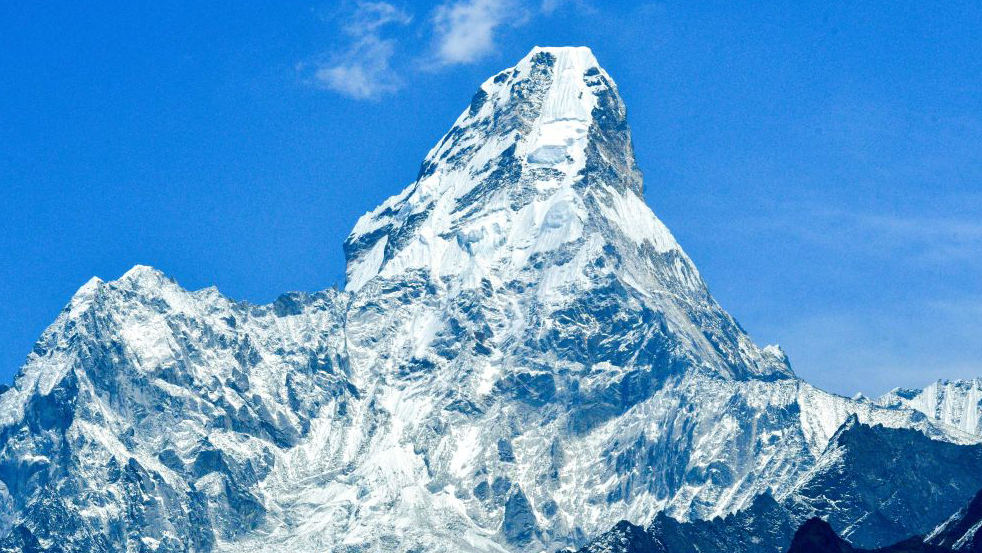

He was nominated for a Piolet d’Or, the most revered award in mountaineering circles, for his Khumbu Express Expedition in 2005. The adventure saw him take on the north face of Cholatse, the east face of Tawoche and the northwest face of Ama Dablam, one of the world's most beautiful mountains, solo. When asked about his free solo approach to mountaineering and his relationship with fear he admitted that there’s a certain amount of trepidation when facing up to a big climb or project but that, “When you set off, when you’re climbing, there can be no room for doubts or hesitation.”

His relationship with Annapurna, arguably the most dangerous of the world’s 8,000-meter peaks, is chequered to say the least. In 2007, he was struck by rockfall on the mountain. It knocked him unconscious and he plummeted 1,000 feet. When he came to, he was dazed and confused, aimlessly staggering around glaciated terrain. He was lucky that a team member spotted him and was able to guide him to safety.

The next year, he heroically came to the aid of Spanish climber Iñaki Ochoa, who had suffered a stroke high on Annapurna’s huge South Face. Steck was camping below the face when he received a distress call from Ochoa’s partner Horia Colibasanu, who had become pinned down with his stricken friend. Steck was not fully acclimatized and was equipped with trekking rather than his mountaineering gear, which was stashed further up the mountain. Nevertheless, without too much thought for his own safety, he and fellow Swiss climber Simon Anthamatten set out to rescue the pair.

What followed was a remarkable rescue effort, with several other alpinists joining the Swiss duo. Steck managed to reach Ochoa and inject him with steroids, but the Spaniard died in his arms. Nevertheless, Colibasanu was rescued, as the team managed to avoid the avalanches plaguing the face to get back to safe ground.

His ascent of the north face of Nepal’s Tengkampoche, alongside Anthamatten, earned him his first Piolet d’Or in 2009. They named the ridiculously steep mixed face Schachmatt, the German word for Checkmate.

Annapurna South Face and confrontations

In October 2013, Steck achieved a staggering ascent of Annapurna’s immense South Face. He climbed via new route, without supplementary oxygen and was the first person to ascend the face solo. British alpinist and friend Jon Griffith described the effort as “truly phenomenal – a mind-blowing effort”, while the legendary British mountaineer Chris Bonington proclaimed that “Himalayan climbing is very much alive”.

Others also lauded his efforts, though controversy soon followed. Many questioned the veracity of Steck’s climb – as he’d lost his camera and neglected to carry a GPS device, meaning there was no concrete evidence of his success. However, two sherpas witnessed seeing the light from his head lamp above all the significant challenges on the mountain, which corroborated his version of events. In any case, he was awarded his second Piolet d’Or for his achievements and it’s fair to say that it was one of the boldest ascents in Himalayan climbing history.

Earlier in 2013, Steck, Griffith and Italian Simone Moro were attempting the same Everest and Lhotse traverse that would prove fatal for Steck in 2017, when an altercation erupted. The three were passing sherpas who were placing fixed ropes ahead of the main climbing season. The sherpas claimed that ice was dislodged by the trio’s passage and that one of sherpas was struck, which Steck, Griffith and Moro deny.

Back at camp 2, tensions boiled over and the three Westerners were assaulted, with one of the sherpas reputedly waving a pocketknife. Moro said that death threats were made and, fearing for their safety, the three climbers fled back to basecamp. The events went viral, which saddened Steck greatly.

The 4,000ers and discoveries on Shishapangma

The summer of 2015 saw Steck climb all 82 of the 4,000-meter peaks of the Alps in a single 62-day push without using motorized transport. A similar feat has since been achieved in 2024, when Kilian Jornet stunned the world by completing it in a staggering 19 days.

In 2016, Steck and German climbing partner David Göttler discovered the bodies of Alex Lowe, one of America’s greatest ever mountaineers, and David Bridges on Shishapangma. Lowe and Bridges had been climbing with fellow great Conrad Anker in 1999 when a serac collapsed and the resulting avalanche swept the two of them to their death, while Anker sustained serious injuries.

Death on Nupste

In 2017, Steck turned his attention to the traverse of Everest and Lhotse, enchaining the world’s highest mountain, via the coveted Hornbein route on Everest's West Ridge. The Hornbein route was put on the map in 1963 when Americans Willi Unsoeld and Tom Hornbein became the first in history to traverse a major 8,000-meter peak. Jon Krakauer, in his classic book Into Thin Air, wrote that, “Hornbein's and Unsoeld's ascent was – and continues to be – deservedly hailed as one of the great feats in the annals of mountaineering.” Steck’s went beyond this – an ambitious plan and would have been an incredible achievement had he pulled it off.

Steck was acclimatizing on Nupste on April 30, somewhere between Camps 1 and 2, when tragedy struck. It’s not known what caused the fall, only that he’d taken a fatal 1,000-meter tumble into the Western Cwm. He was 40 years old.

His legacy of bold ascents in the Alps and the Himalayas ensures that he too will always have a place in the annals of elite mountaineering. He’s survived through his wife Nicole.

Alex is a freelance adventure writer and mountain leader with an insatiable passion for the mountains. A Cumbrian born and bred, his native English Lake District has a special place in his heart, though he is at least equally happy in North Wales, the Scottish Highlands or the European Alps. Through his hiking, mountaineering, climbing and trail running adventures, Alex aims to inspire others to get outdoors. He's the former President of the London Mountaineering Club, is training to become a winter mountain leader, looking to finally finish bagging all the Wainwright fells of the Lake District and is always keen to head to the 4,000-meter peaks of the Alps. www.alexfoxfield.com