Do you have to pay for mountain rescue?

We clear up a common misconception about the cost of a mountain rescue effort which is leading many hikers to avoid or delay calling for help

Do you have to pay for mountain rescue? If you’re injured, sick or lost on a mountain and can’t get down by yourself, this question should be the furthest thing from your mind, and yet there are countless cases of people delaying and even evading rescue for fear of receiving an astronomical bill in return.

There’s the story of a climber on Mount Baker who descended 3,000ft on a fractured ankle before submitting to rescuers. The lost trail runner in Tucson who hid from his rescuers overnight to avoid a bill. A woman who delayed in calling mountain rescue for hours while she searched for her missing husband at high altitude on the Colorado 14er Mount Evans in increasingly deteriorating conditions. And a paraglider who had crashed into a mountain and tried to slide down scree slopes with what would turn out to be permanent spinal injuries rather than have a team stretcher him out.

What would possess these folks, who statistically speaking all had working cell phones, to delay in dialing 911? In each case, it comes down to a persistent myth that if mountain rescue comes to stretcher or helicopter you off a mountain, you’ll be hit with a bill for $10,000. This number comes up over and over again in mountain rescue testimonials about people avoiding or delaying rescue. Why? In part, it’s probably because of news stories like one about a hiker who sprained his ankle in Colorado who was facing charges of $10,000 after being rescued from Clear Creek Canyon in 2007. The truth of the matter, however, is that he wasn’t helped by mountain rescue at all, but by Golden firefighters, and it was them who billed him. Two years later, the case was still in dispute, the bill had been halved, and it’s not clear that he ever paid anything.

It also seems likely that for American hikers and trail runners in particular, resistance to calling for help, or receiving help, is because they do routinely get hit with colossal bills for medical services, even when they’re insured, making them extra wary of any type of emergency or medical assistance.

And for some, there’s bound to be an element of shame to admitting you overestimated your capabilities, forgot to bring your water bottle or attempted to hike a 14er wearing flip flops.

But the $10,000 mountain rescue bill is just a myth. If you get lost on a mountain and they assist you on coming down, mountain rescue will not bill you for their services in the US or the UK. Mountain rescue, which falls under a wide network of largely volunteer-based search and rescue (SAR) agencies including the coastguard, exists to save lives – not just the lives of those who can afford to pay for it (why this same ethos isn’t embraced by the wider healthcare system in the US is another article altogether).

Colorado SAR, who provided resources for this article, state that not only do they believe mountain rescue to be an essential service and take pride in their volunteer work, but that they further believe it helps to sustain the Colorado way of life. Charging for their services, especially in a punitive context, does nothing to further the outdoors-focused culture here and could even damage Colorado outdoor tourism.

Advnture Newsletter

All the latest inspiration, tips and guides to help you plan your next Advnture!

Yes there are some dubious calls – the Swedish couple who called for an air ambulance on a hike because they were tired, even though there was a cottage nearby where they could have rested (they opted to pay for the helicopter ride anyway), and those late night walkers on Arthur’s Seat in Edinburgh who called mountain rescue because they became scared of the highland cows. But if you are injured, lost or actually too tired to call down, you shouldn’t hesitate to call for help.

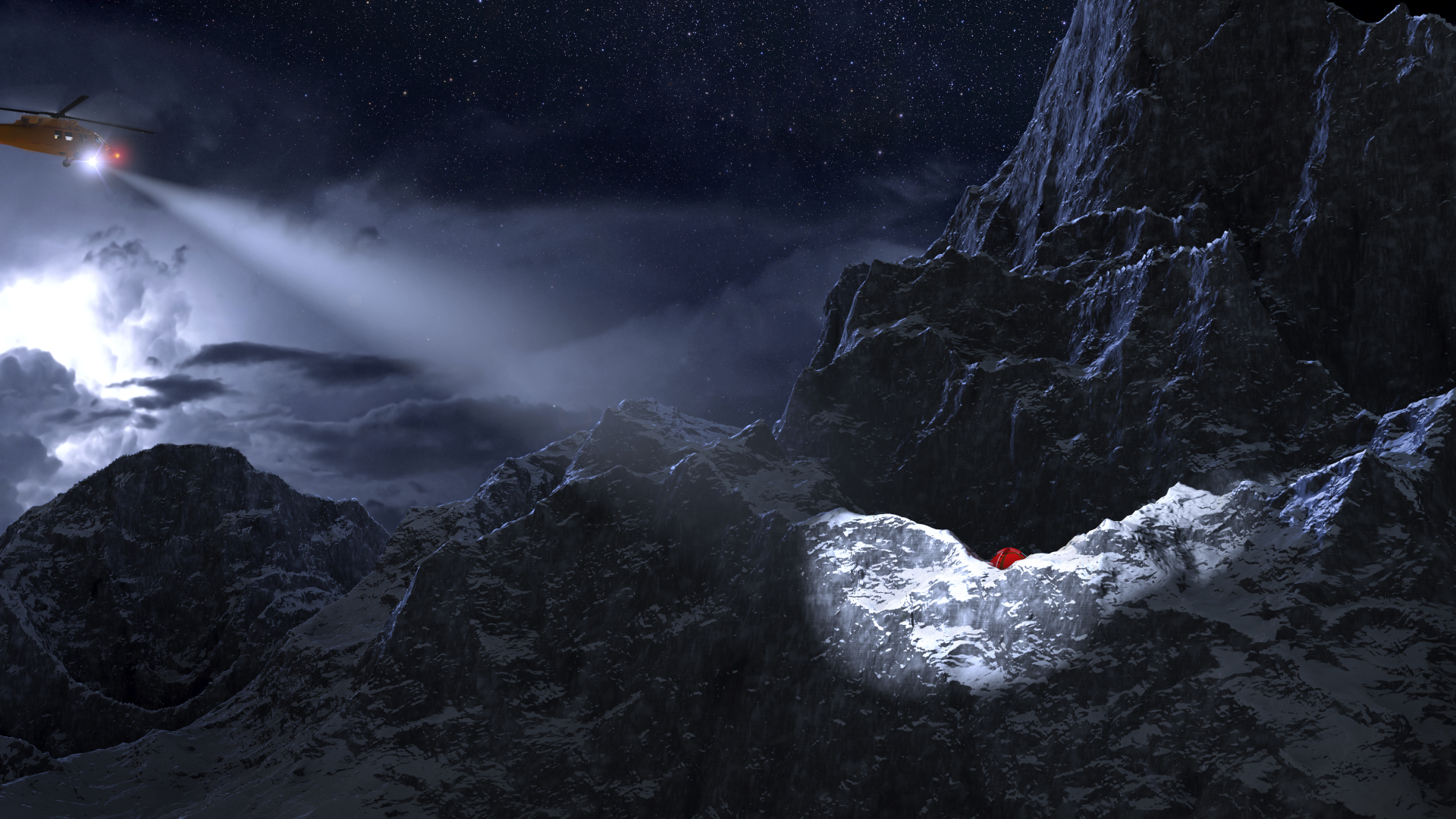

Failure to dial 911 when you need help can obviously increase your risk of exposure and hypothermia as well as sustaining further injuries, but it doesn’t just increase your risk – making a call at 11pm that should have been made at 3pm can mean rescuers themselves have to spend the night on the mountain, which is riskier for them and can end up costing them more as they use more resources.

Now all of this said, there may be charges associated with getting rescued from a mountain, it’s just that those charges won’t come from the mountain rescue team. If you call 911 straight away when you fall into trouble and a team is dispatched to find that you only need navigational assistance or minor first aid, they might guide or stretcher you down the mountain and from the trailhead, you may be able to get home yourself or call a friend for a ride.

But if your rescue involves an ambulance that’s waiting for you at the trailhead, in the US you will have to pay for that ambulance, either out-of-pocket or from your insurance deductible. As you’ve probably already realized then, any medical care you receive at the hospital will also come with charges, and those can be astronomical – let’s not forget the New Zealand woman who fell while rock climbing in Yosemite National Park and was hit with a $1.2 million hospital bill. Just because SAR exists to save your life, it doesn’t mean they provide insurance against injury.

Then there are the cases where you could face criminal charges for your conduct. A recent and high profile example of this was a Utah doctor who faced, you guessed it, a $10,000 fine after misleading mountain rescue and impeding an investigation after his climber partner fell whilst climbing Mount Denali. Such cases are the result of reckless and unlawful behavior, however, not failing to lace your hiking boots properly and tripping over, and charges would be filed by a prosecutor, not mountain rescue, who take no official position in such matters.

So we can’t say that any incident in the mountains wouldn’t cost you a dime, but surely a dime is better than permanent injury or death, and remember, the sooner you call, the more damage you can potentially avoid.

What you can do is prepare. Check the conditions. Dress in hiking layers. Tell someone where you are going. Know how to survive a night on a mountain. And if things go off course, ask for help.

Julia Clarke is a staff writer for Advnture.com and the author of the book Restorative Yoga for Beginners. She loves to explore mountains on foot, bike, skis and belay and then recover on the the yoga mat. Julia graduated with a degree in journalism in 2004 and spent eight years working as a radio presenter in Kansas City, Vermont, Boston and New York City before discovering the joys of the Rocky Mountains. She then detoured west to Colorado and enjoyed 11 years teaching yoga in Vail before returning to her hometown of Glasgow, Scotland in 2020 to focus on family and writing.