What is dry tooling in climbing? Axes at the ready!

As it continues to surge in popularity, we take a look at dry tooling, its history and how the pursuit emerged from mixed climbing

A handful of mountaineers stroll towards the cliffs of Saltdean, ice axes at the ready, crampons glinting in the sun, carabiners and quickdraws jangling as they walk. They’re ready to practise their ice climbing and mixed climbing techniques, using the cliffs as a training ground for bigger adventures in the Scottish Highlands or the European Alps. If you’re unfamiliar with Saltdean’s cliffs – and I’m guessing you will be – you might not raise an eyebrow at this. That is, until someone tells you that the rock face above these would-be alpinists is made of chalk rather than ice.

The mountaineers in question have travelled down to England's south coast from London, eager to try their hand at a spot of dry tooling on the white cliffs. The closest they’ll get to ice on this trip will probably be when one of them orders a coke from a local cafe during lunchtime.

However, like proper ice climbing, there’s a hefty dose of commitment to what they’re undertaking. Just as ice is ephemeral – there one day, gone the next – so too is Saltdean’s notoriously crumbly chalk. It’s a face that sees significant erosion every year and anyone climbing here does so at their own risk (it’s not something I’d necessarily endorse).

However, dry tooling isn’t limited to chalk. Indeed, you can take your dry tooling approach to pretty much all kinds of rock. So, just what is dry tooling exactly? Here’s a history of the pursuit and how it evolved from mixed climbing.

What is dry tooling?

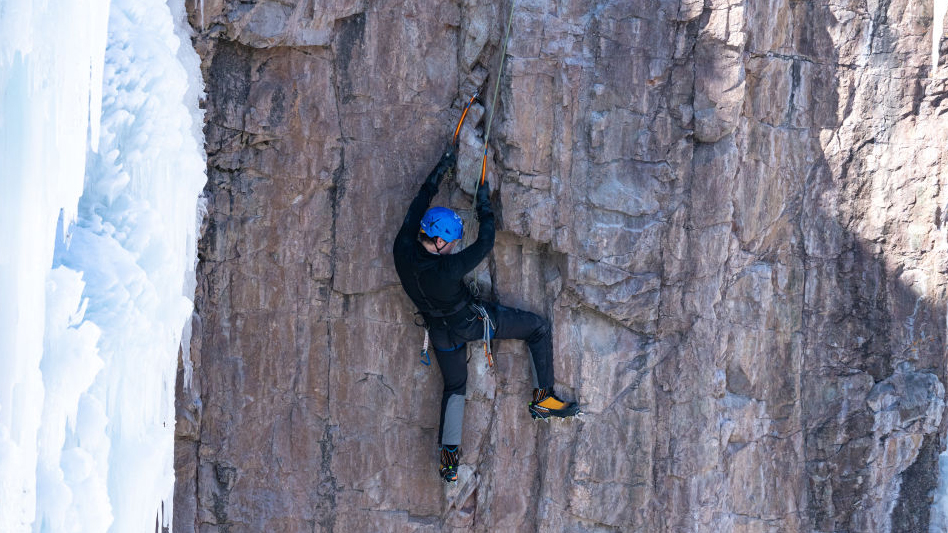

Dry tooling is a form of climbing that uses technical ice axes and crampons but rather than climbing ice and snow it takes place on routes with nothing but bare rock. Dry tooling techniques evolved from mixed climbing, a form of mountaineering where climbers negotiate a mixture of snow, ice and rock during a climb.

In terms of protection, a dry tooling rack bears more resemblance to a standard climbing rack, with none of the the screws used when ice climbing. Almost all dedicated dry tooling routes are bolted in the same way as sport climbing routes, meaning climbers don’t have to place their own protection as they progress, other than clipping the rope into quickdraws.

An advantage of dry tooling is that climbing can take place all year round, even when the rock is wet, ironically. Indeed, many dedicated dry tooling routes take place on rock that’s often too damp to be developed into a sport climbing route. However, a criticism sometimes levelled at the pursuit is the damage it can do to the rock and to fragile ecosystems. This is one reason you don’t tend to find dry tooling taking place on established rock-climbing routes.

Advnture Newsletter

All the latest inspiration, tips and guides to help you plan your next Advnture!

The way a climber uses their crampon points and the narrow pick of an axe to scale a route demands a mixture of precision, strength and flexibility. As with sport climbing routes, the fact the climber doesn’t have to think about placing protection frees them up to focus solely on the technical challenge of the climb.

Meet the expert

Former President of the London Mountaineering Club, Alex is passionate about exciting outdoor pursuits. He enjoys all forms of climbing, whether trad, sport, scrambling, alpine mountaineering or taking on snow-covered peaks in winter.

History of dry tooling

Dry tooling evolved from mixed climbing, a form of mountaineering where a mixture of ice and rock is negotiated during an ascent. Mixed climbing techniques have long been used by mountaineers and alpinists in everywhere from the Alps and Scotland, to the Himalayas and the Rockies.

In all of these cases, it was natural for climbers to climb sections of rock while still wielding axes and wearing crampons – the alternative being to keep on putting them away. This is more straightforward with axes but taking off and putting on crampons is a time-consuming business. Besides, the rock would often be so cold that using axes to climb was preferable to bare hands or the imprecision of hiking gloves. Indeed, the precision offered by crampon spikes and an axe's pick on tiny ledges and in narrow cracks opened up a whole new world of possibilities.

Jeff Lowe, one of America’s greatest ever mountaineers and recipient of the Piolet d’Or Lifetime Achievement Award in 2017, is often cited as the man who ushered in the era of modern dry tooling. It was 1994 and Lowe was climbing in the Rigid Designator area near Vail, Colorado. Rather than climbing The Fang, a frozen waterfall hanging down the centre of an overhanging amphitheatre, he opted to try out neighboring rocky overhangs instead. This provided an alternative way to access Octopussy, a precariously hanging icicle. Not only was a new route born, but the climb breathed life into a whole new pursuit.

After this climb, dry tooling for dry tooling’s sake became a thing, rather than it simply being part of mixed climbing. Many still use it to train for ice climbing, or to maintain their technique during the warmer months. However, others are dry tooling specialists and the approach has developed into a key part of competition ice climbing – which we'll come to in a mo.

In 2016, British alpinist Tom Ballard raised the standard by climbing the D15-graded A Line Above the Sky on the flanks of Marmolada, the highest mountain in the Dolomites, the first of its difficulty level. Ballard achieved much in the mountaineering world before his life was tragically cut short on Nanga Parbat in 2019, at the age of 30. He was the son of legendary British mountaineer Alison Hargreaves, who also lost her life in the high mountains, on K2 in 1995.

In recent years, the grades have been pushed further by Italian alpinist Matteo Pilon, who sent Altheia in 2021 and Téleois in 2024, both at Ponte nelle Alpi in northern Italy. Both were graded as D16, with Téleois even being given a cheeky +. Which brings us nicely to…

How are dry tooling climbs graded?

Every niche has its own climbing rating system and dry tooling is no different. It shares the system with mixed climbing, ascending numerically with an M to signify the style and occasionally a plus sign to indicate nuances in difficulty. Comparing between mixed climbing grades and the Yosemite Decimal System and other standard rock climbing grades is difficult, as the variables are many. However, in 1996, Jeff Lowe estimated that an M8 was equivalent to a 5.12 route.

A ‘D’ is often used to signify that a mixed climb was completely free of ice, therefore a pure ice tooling route. In 2010, in response to certain moves and equipment that took away from the challenge of dry tooling, French climbers introduced DTS: Dry Tooling Style. This indicates that the climb was done in a pure style.

The table below is taken from the Alpinist's Climbing Grade Comparison Chart guide.

Grade | Description |

|---|---|

M1 to M3 | Easy. Low angle; usually no tools. |

M4 | Slabby to vertical with some technical dry tooling. |

M5 | Some sustained vertical dry tooling. |

M6 | Vertical to overhanging with difficult dry tooling. |

M7 | Overhanging; powerful and technical dry tooling; less than 10m of hard climbing. |

M8 | Some nearly horizontal overhangs requiring very powerful and technical dry tooling; bouldery or longer cruxes than M7. |

M9 | Either continuously vertical or slightly overhanging with marginal or technical holds, or a juggy roof of 2 to 3 body lengths. |

M10 | At least 10 meters of horizontal rock or 30 meters of overhanging dry tooling with powerful moves and no rests. |

M11 | A ropelength of overhanging gymnastic climbing, or up to 15 meters of roof. |

M12 | M11 with bouldery, dynamic moves and tenuous technical holds. |

Competition ice climbing

A lot of dry tooling takes place indoors on artificial walls purposefully designed to replicate something akin to pursuit of ice climbing. Competition ice climbing is often nothing more than indoor dry tooling, though some events also take place on artificial ice walls or outside on real ice. However, most routes in a competition like the Ice Climbing World Cup take place on dry, artificial walls, often made out of plywood.

One of the reasons artificial walls are favored, is that vertical ice is actually relatively easy to climb for the world’s elite ice climbers, who meet their match on more difficult, overhanging routes. Then there’s the fact that, when climbing on ice, each competitor changes the course with the holds they smash into the face on the way up. So, the person going last would benefit from the fact that those who went before have already figured out the best way up and left a load of helpful pick placements in their wake. Not exactly a fair competition.

Alex is a freelance adventure writer and mountain leader with an insatiable passion for the mountains. A Cumbrian born and bred, his native English Lake District has a special place in his heart, though he is at least equally happy in North Wales, the Scottish Highlands or the European Alps. Through his hiking, mountaineering, climbing and trail running adventures, Alex aims to inspire others to get outdoors. He's the former President of the London Mountaineering Club, is training to become a winter mountain leader, looking to finally finish bagging all the Wainwright fells of the Lake District and is always keen to head to the 4,000-meter peaks of the Alps. www.alexfoxfield.com