Chucking bombs, saving lives and fresh tracks: a day in the life of ski patrol

We spent the day with Verbier ski patrol learning everything they do to control avalanche risk, rescue injured skiers and keep the mountain safe

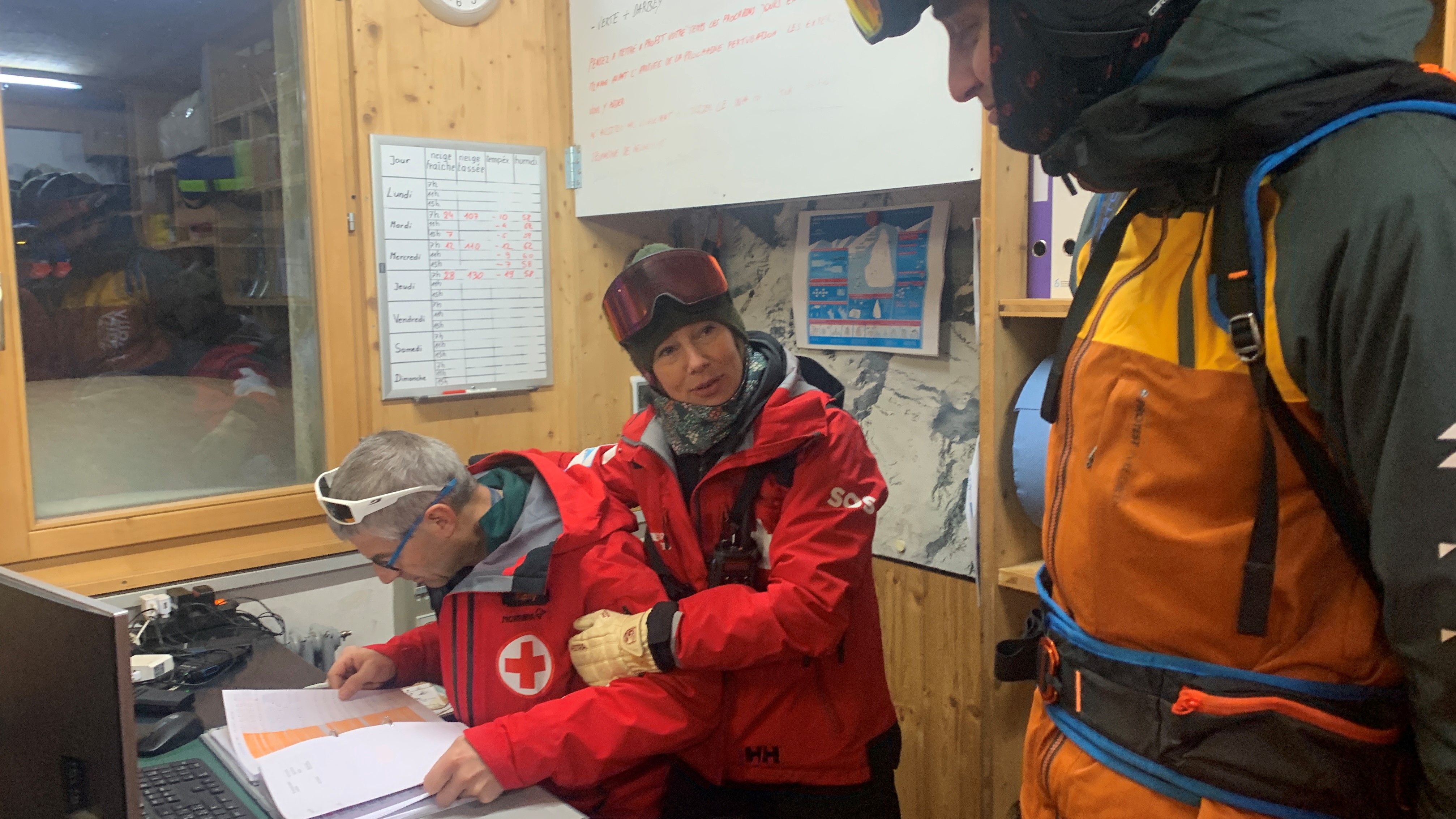

It’s 7:15am and eight members of the Verbier ski patrol are clustered around a table in a small room nearly halfway up the mountain, dressed in their matching Helly Hansen red ski uniforms. It’s pitch dark outside and they’ve ridden the gondola up here to Les Ruinettes for their morning briefing.

Despite the early hour and bracing temperatures (it’s -19°C), the energy is high – 11 inches of fresh snow fell overnight on top of over a foot in the preceding two days and they’re expecting a busy day and great skiing. They chat animatedly in French while knocking back expressos from a machine that sits on the table. Other patrollers come and go, grabbing gear from their lockers and in the corner, the head of security, a gray-haired gentleman named Rafi, sits quietly at his desk and figures out which areas of the mountain need to be bombed this morning to mitigate the risk of avalanche.

Within minutes, Rafi has paired the team members up and ordered one duo to go to the bunker on the mountain to fetch the explosives and fuses needed to stabilize the terrain. The room empties out and we’re left with Victoria Jamieson, a petite spitfire of a ski patroller who’s been tasked with taking the group of journalists around the mountain today because, she says, “they think I’m nice".

Jamieson can’t stand at much more than five feet tall, and that's in ski boots, but you can instantly tell she’s a bit of a powerhouse. In 2008, she joined ski patrol as the first woman on the team after her friend was seriously injured by rockfall during a two-day expedition of an arete that the pair were climbing together.

“At that time I was doing a lot of mountaineering and it made me want to understand what to do in the case of an accident.”

By the time she finished the intensive training, a spot had opened up on the crew and she landed the job. Fifteen years later, she’s still only five women out of a team of 32, but she commands instant respect among her young crew.

We give the patrollers a few minutes to get ahead of us then we load up on another gondola and continue our journey to a spot higher up on the mountain, where we make our way to a small wooden hut while the sun begins to make its way up over the surrounding Alps and a picture perfect day begins to take shape.

All the latest inspiration, tips and guides to help you plan your next Advnture!

We’re dressed for the elements – Helly Hansen has specifically kitted us out in ski socks, base layers, thermals, ski salopettes and jackets, ski gloves, and neck gaiters to cover every scrap of exposed skin – but still fingers and toes begin to nip instantly in these conditions. Make one wrong move – forget a layer, lose a glove or leave your nose exposed, and frostbite becomes a very real possibility. That’s all part and parcel of being a ski patroller, but we’re just journalists who love skiing, and a little less hardy, so we cram ourselves into the hut for warmth, and Jamieson explains that a computer on a desk here is where the bombing is controlled from.

The explosives are about the size of a can of Coke, and consist of a combustible mix of propane and oxygen that, when detonated remotely, will trigger an avalanche so that a skier coming along a few hours later won’t. This is a common tactic in North American and European ski resorts, and for this reason, even though avalanches killed 17 skiers in the US last year, none of those fatalities occurred in bounds.

Most of the snow last night fell down lower on the mountain where the slopes aren’t as steep, thanks to a cloud inversion, so patrol only needs to chuck a couple of bombs this morning. Above us, another gondola leads up to Mont Gele, a pyramid-shaped peak which is one area they’ve identified as needing mitigation work.

Unseen by us, a ski patroller is already up there and has thrown the dynamite. Outside, we huddle together in the frigid conditions and hear him radio down to the patroller inside the hut that the bomb is ready. A click of a mouse and a few seconds later, we cheer as we see the flash on the hillside, hear a loud bang, then watch a small avalanche slide down the slope.

Jamieson receives word over the radio that avalanche mitigation is complete for the day, which means that incoming skiers can enjoy the new snow safely – so long as they stay on the marked runs, or pistes as they’re known in Europe.

“We only secure the piste, we don’t secure the off-piste, so if people go off-piste here in Europe, they have to take responsibility for themselves,” warns Jamieson.

This is the one thing that she wants people to know above all about her work – if you ski off-piste and get in trouble, ski patrol isn’t obligated to come and help you. They might, but that decision is down to the head of security to decide whether it’s safe for the patrollers.

As in a skiing scenario, you always have to accept that your chosen winter sport carries with it inherent risks. Though I’ve been lucky enough never to have needed rescue in my thousands of days of skiing over the decades, it occurs to me now how much of that has been made possible, behind the scenes, for these hard-working heroes, and for that I’m thankful.

It’s after 8am now, the snowy peaks are tinged with pink, and it’s time to ski down the mountain to sweep the runs and make sure they’re ready for the resort to open at 8:45am. We follow along as the patrollers check the poles that mark the pistes, put up signs when needed, and though it’s all very procedural, it’s hard to convey this experience as routine when you’re skiing perfect, untouched snow on an empty mountain in the Alps at sunrise. This morning drill, for Jamieson, easily makes up for the brutally early starts, the bitter temperatures, and the hard physical work.

“The scenery is so incredible, so beautiful. First thing in the morning, you go up there and it’s just so breathtaking. You don’t ever get bored of that.”

Once the mountain is open, the ski patrollers stay busy throughout the day, ensuring the runs remain in good shape, and of course, responding to callouts. They might have ensured you’re safe from avalanches on the pistes, but they can’t keep you safe from yourself or other skiers. Jamieson tells us that the last two years have seen a spike in the number of callouts for her team, though no one is sure why.

If you fall skiing and break your leg, ski patrol will be your first responders. In life-threatening situations, a helicopter might arrive, but if they can, patrollers will load you up in a toboggan, wrapped up in blankets for warmth and braced against impact as much as possible, and ski down the mountain pulling you behind them. This is highly skilled work and not fun or comfortable for the injured skier, especially in stormy weather.

In Verbier, when you get to the base of the resort, it’s another half hour at least of winding mountain roads to the hospital in Martigny, so if the ambulance can’t meet you there, ski patrol may need to take you all the way. Unsurprisingly, it’s this part – seeing badly injured skiers, some of whom may be children – that Jamieson says is the hardest part of the job.

“Accidents can happen to everybody, but I think it’s important to be physically in good shape, if that’s possible, and just always be aware of people around you because there's a lot of people skiing at the same time so it’s good to be a little respectful of what’s going on around you. And people ski really fast,” she warns.

It’s true that, during this week in January at least, the level of skiing at the resort is noticeably advanced, but with that proficiency comes a certain velocity combined with risky maneuvers that can easily be catastrophic. By the time we’ve stopped for lunch, we’ve already seen a helicopter making a landing near the top of the mountain to help someone for whom the picture-perfect day hasn’t ended as well as it began.

The last chair and gondola run at 4:15pm, then Verbier is closed for the day. Skiers pour into bars and restaurants in the village below and a festive atmosphere kicks in as people compare stories of the day over Swiss beer, munch on giant salads, and play games of Jenga. Though the sun doesn’t set until after 5pm, in January the surrounding mountains mean it’s already getting dark.

Up on the resort, ski patrollers are still hard at work, performing closing sweeps – essentially making sure every skier has gotten off the mountain and the pistes are clear. The ones that are working again tomorrow don’t have much more than 12 hours to get off the mountain, wind down, get home, eat and rest up before another long, strenuous and enjoyable day begins chucking bombs, saving lives and skiing fresh tracks. It's a day of the life of a ski patroller.

- Best ski gloves: for warmer hands all day long

Julia Clarke is a staff writer for Advnture.com and the author of the book Restorative Yoga for Beginners. She loves to explore mountains on foot, bike, skis and belay and then recover on the the yoga mat. Julia graduated with a degree in journalism in 2004 and spent eight years working as a radio presenter in Kansas City, Vermont, Boston and New York City before discovering the joys of the Rocky Mountains. She then detoured west to Colorado and enjoyed 11 years teaching yoga in Vail before returning to her hometown of Glasgow, Scotland in 2020 to focus on family and writing.