Right to roam: what does it mean for your outdoor adventures?

We define what your right to roam is, consider where it applies and what it means for your outdoor adventures

You don’t have the right to roam everywhere. After all, you wouldn’t like it if Jerry from up the road suddenly appeared in your garden, prodding around at your daffodils and stomping over all over your vegetable patch. You’d also be a bit bemused if Christine from across the street walked her muddy shoes across your living room and started helping herself to water from your tap. How dare they? This is your private land!

In this day and age, all of the land that we want to explore – whether it’s with our hiking boots, our bikes, our camper vans or our cross-country skis – is owned by someone. Land has myriad uses, so it’s no surprise that landowners seek to utilise it and profit from it. Agriculture, mining, renewable energy, forestry, military training, education and scientific study are just a handful of the many ways the land is used.

And that’s before we’ve even considered leisure activities like hiking, climbing, cycling, horse-riding, shooting, trail running, skiing, paragliding, camping… The list goes on. Of course, many stakeholders welcome these pursuits, as they bring visitors to the region, which helps the economy. However, for all of this to coexist together, there must be compromises and considerations from all parties.

The right to roam

The right to roam – sometimes referred to as ‘freedom to roam’ or ‘everyman’s right’ – is one such compromise. In simple terms, your right to roam is your right to access certain areas of privately or publicly owned land for recreation or exercise. Thanks to the campaigning of early access pioneers, there are vast swathes of countryside that are open to our best hiking shoes.

In America, hundreds of millions of acres of land – over a fifth of the nation’s total land area – is legally accessible and open for your enjoyment. In the UK, there are differences between the individual nations, but generally people have a right to roam in uncultivated open countryside – such as mountain, moor, heath and down – and registered common land.

However, many long-distance trails and thru-hikes pass through industrial or agricultural land. So how is it that people can still access such paths? Well, the precise laws vary in every country but generally access falls into two categories: rights of way and access land.

Rights of way

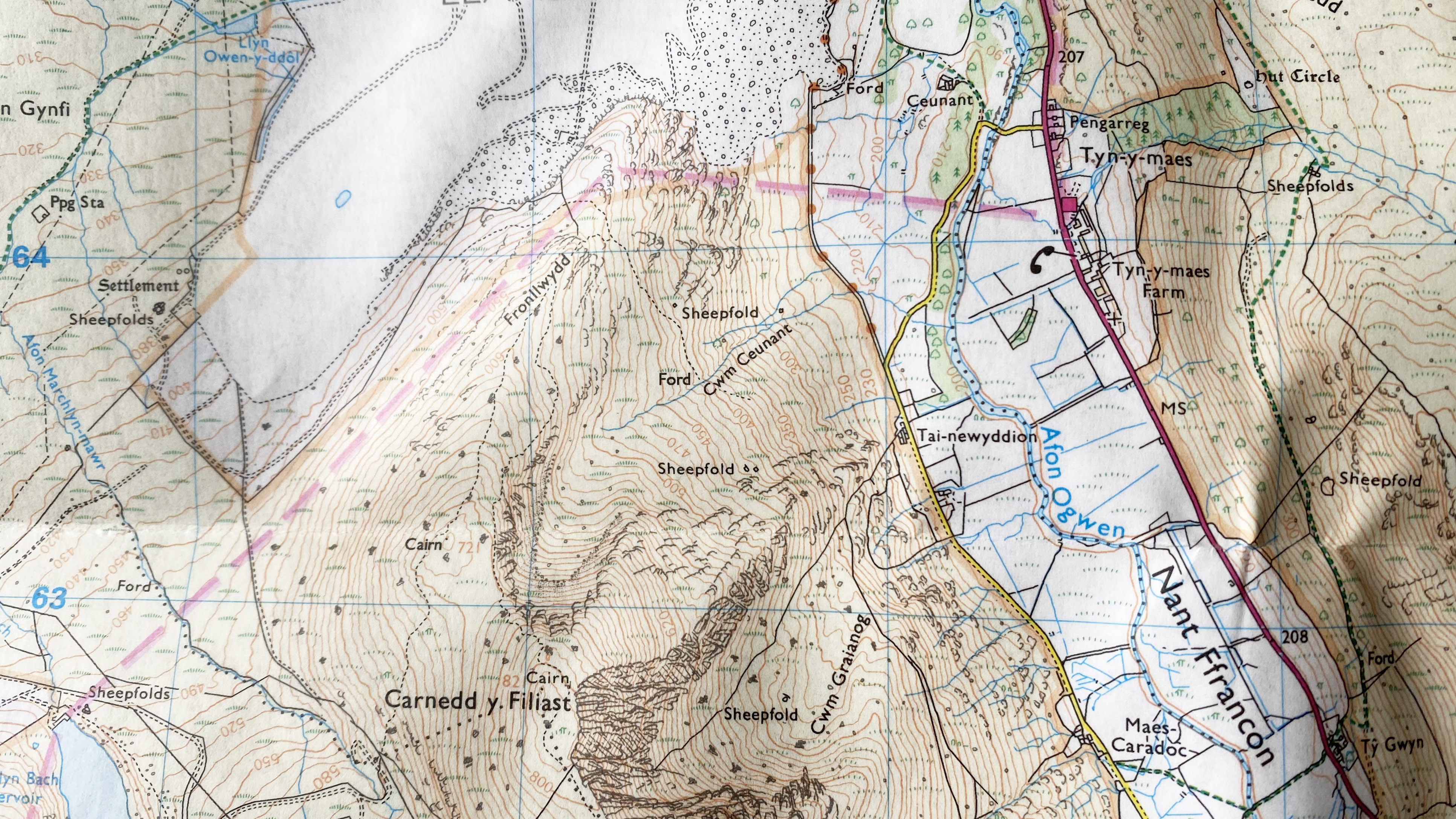

You are allowed to walk through certain private lands on rights of way (sometimes called ‘permissive paths’). These are usually signposted as a public footpath or similar. On a topographical map, a footpath, byway or bridleway will be clearly indicated by a line.

Advnture Newsletter

All the latest inspiration, tips and guides to help you plan your next Advnture!

Let’s use the example of a path across a farmer’s field. Although you have the legal right to follow the path from one end of the field to the other, you do not have the right to leave the path and start exploring the field. If you’re hiking with a dog, it should be kept on a leash. On your map, the field will be represented in white, indicating private land.

Access land

Access land is where you can wander freely, leaving the path should you choose. Today, places like national parks and other specially designated areas contain huge areas of access land for us to explore. However, national parks can still contain thousands of acres of agricultural, industrial and forestry land that are not free to roam around on. So just because you’re in a national park, doesn’t mean you can go everywhere. On the flip side, even if a place isn’t in a national park or a specially managed area, you may still have a right to roam among it, depending on the law of the country you are in.

Mostly, it’s a case of using your common sense; you should be able to tell the difference between wild, open land and cultivated farmland. Though there can be an overlap between the two. For example, cattle are often reared on access land. This is where you have a responsibility to respect local communities by considering the way you use and interact with your surroundings. Basically, leave the environment as you found it, try to keep your impact to a minimum and keep your dog under control. If you are unsure of whether you are on access land or not, it should be indicated by the shading on your topo map, GPS or hiking app.

Just because you can, may not mean you should

There are other major stakeholders who sadly don’t get a say in how land is used: the wildlife that has almost been entirely squeezed out of our natural landscapes. Conservation efforts and the rewilding of the countryside gain pace every year, which is wonderful to see. Most outdoor enthusiasts have at the least an appreciation of nature and are receptive to ways that they can help to protect it.

The vast majority of our national parks and hiking destinations are criss-crossed by trails. Your right to roam means that you do not necessarily have to stick to them. Trail runners will often take a quicker line than a zigzagging trail, rock scramblers by their very nature will leave paths behind and walkers will often go hiking with a dog in the mountains.

Bear in mind that paths are in place to help to protect our precious environments from the potentially devastating impact of the thousands of visitors who come to enjoy them every year. We are the custodians of these landscapes and have a duty to look after them for the next generation and for the wildlife that inhabit them. When you go ‘off-piste’ you have an impact on the heathers, mosses and other plant life that eke out an existence in these wild places. When you scramble, stick to the rock and be mindful not to damage rare alpine flora. Before you bring your dog, check online to see if there are ground nesting birds in the region; you may have to keep Rex on the leash.

In short, remember that your right to roam is a privilege. To quote the Peter Parker principle: “With great power comes great responsibility.”

Alex is a freelance adventure writer and mountain leader with an insatiable passion for the mountains. A Cumbrian born and bred, his native English Lake District has a special place in his heart, though he is at least equally happy in North Wales, the Scottish Highlands or the European Alps. Through his hiking, mountaineering, climbing and trail running adventures, Alex aims to inspire others to get outdoors. He's the former President of the London Mountaineering Club, is training to become a winter mountain leader, looking to finally finish bagging all the Wainwright fells of the Lake District and is always keen to head to the 4,000-meter peaks of the Alps. www.alexfoxfield.com