"Ultimately, I’m not unaware of the drop" – 5 lessons learned from blind climber Jesse Dufton

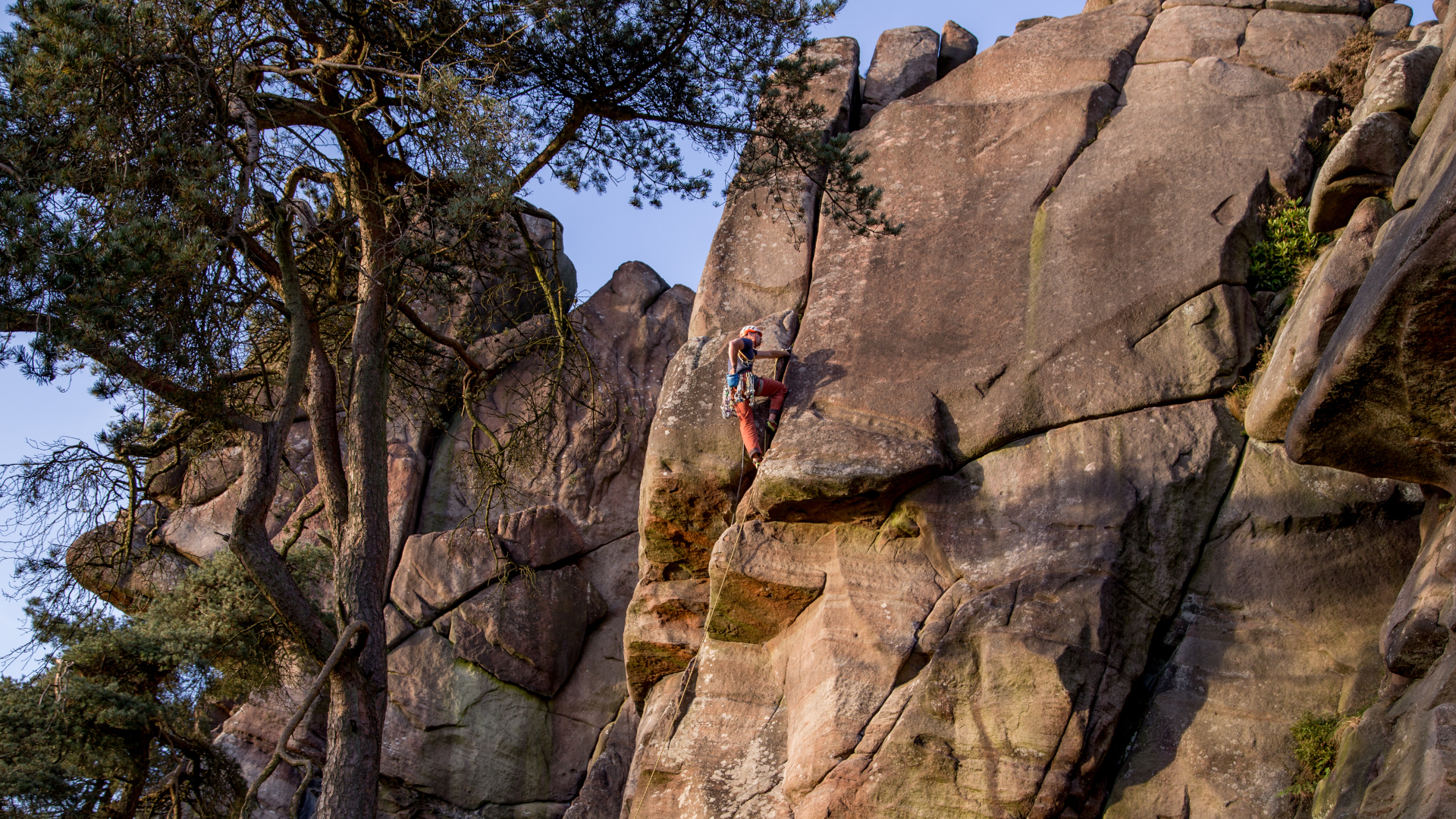

He is best known as the first blind person to lead climb the Old Man of Hoy

Jesse Dufton started climbing at the tender age of two, not long after he learned to walk, and several years before he would learn he was going blind.

“When I was young, my eyesight was terrible, but because that’s all I knew, I’d got very used to masking it."

It was only when he started school that he got his eyesight properly diagnosed and his parents finally understood why their young son had always sat so close to the television screen.

By the age of 11, Dufton had about 20 percent of blurry central vision and no peripheral vision left, and today has lost his remaining useful sight. It wasn’t until he met his future wife at university, and spoke to her about his sight that he even discovered other people could see leaves on trees.

“I could see a tree but never knew that everyone else could see the individual leaves and it's not just a green blob to them."

For many people, this might spell the end of hope for any fledgling athletic career, rock climbing or otherwise, but Dufton’s parents loved climbing, so that's what the Duftons did, on family trad climbing and bouldering trips in Fontainbleau.

“My dad’s really super optimistic and has a can-do attitude and that really shone through," he recalls of his father, a mountaineer and former mountain rescue crew member.

All the latest inspiration, tips and guides to help you plan your next Advnture!

We sat down with Dufton to hear about his incredible journey and find out what lessons he's learned as a blind climber.

1. You don't know what you're missing

Climbing is a sport where many of us would assume a keen sense of sight is required, but according to Dufton, that's not necessarily so.

“When you’re born with something like a visual impairment, you don’t know what you’re missing, so you don’t know that it’s not normal.”

Not knowing what he was missing helped Dufton gain independence. He left home after school and attended the University of Bath, where he followed in his father’s footsteps and joined the mountaineering club. He took up alpine and ice climbing, finding a network of climbing friends that he continues to climb with today, learning to rely on their support while his eyesight continued to deteriorate.

2. It can't get any harder

Dufton isn't just hanging around at the climbing wall with his old university friends these days. He is best known as the first blind person to lead climb the Old Man of Hoy, which is the focus of Alastair Lee’s multi award winning documentary, Climbing Blind.

He's also completed an expedition to Greenland, where he claimed two first ascents of unclimbed mountains in challenging sub-zero conditions. He has led well-known routes on the Isle of Skye, Joshua Tree National Park and the Peak District, and picked up 17 trophies at various Climbing World Cups and other highly regarded competitions, leading him to be selected for Great Britain’s Paraclimbing team.

So, what is it that has led Dufton, seemingly against quite a lot of odds if not all them, to not only pursue climbing, but to excel at it?

“I’m stupid and stubborn,” he muses.

“And it gives me something that I hugely enjoy and a reason to keep on going. Now that I’ve lost all my useful sight, it’s not really going to get any harder for me. I can’t lose any more sight, so it’s just down to me to hang in and go and do the stuff I want to do.”

3. There are worse sports for blind people than climbing

Clinging to a rock wall hundreds of feet above the ground without any visual cues might sound like madness, but unlike some other sports he's tried, Dufton says rock climbing is quite suitable to his disability.

"I’ve tried blind tennis and that just seemed like totally the wrong thing for a blind person to be doing. That’s taking a sighted sport and trying to get a blind person to do it, and it doesn’t really work.”

"But with climbing, if I can find the holds, I’m not doing it any differently to anyone else.”

But while the actual moves might look and feel just the same, it’s finding the holds and placing the climbing gear that adds a whole level of extra challenge.

“For most climbers, placing gear is a really visual thing. They look at the crack, they select the piece of gear, then they put it in and then they check it to see if it’s any good."

Dufton, on the other hand, has to feel the crack with his fingers and then visualize in what it’s like before deciding whether to use a nut or a cam, and what size it needs to be.

4. Straight up is best

Climbing blind has taught Dufton to develop a strong sense of proprioception – that’s your body’s ability to sense movement and location. Though body awareness is useful for any athlete, it has to be much more developed for a blind climber like Dufton.

“Basically, you have to have a 3D map of your surroundings. One thing that makes climbing easier for me is that if I use a hold as a hand hold and I climb up, in a couple of moves time I’m probably going to stand on it, so I try to remember where that hold is in 3D space and then I can put my foot straight on it without having to look at it.”

Consequently, crack climbing is one of Dufton’s favorite types of climbing, because the holds are easy to find – they’re in the crack – while traversing is much more difficult because when he’s moving sideways he doesn’t get to feel the foot holds before he has to stand on them.

5. Danger doesn't disappear when you can't see it

When he’s finished a climb, Molly, who’s also his sight guide, will clean the gear and inspect his placement as she goes, so he can at least get retrospective feedback to help him continue to improve.

So do these carefully-honed systems and methods totally remove the fear factor of climbing for Dufton? Not at all, as it turns out.

“Often people think that being blind is an advantage because when you look down, you can’t see the ground."

"Ultimately, I’m not unaware of the drop. You still know the drop’s there and you still get scared if there’s significant danger. The fact that you can’t see it almost makes it worse, because often if you’ve placed a piece of safety equipment, you don’t know if it’s any good."

But despite that added fear and unknown factors, the benefits of climbing still outweigh the disadvantages for Dufton.

“Especially when I’m leading, I get a sense of independence. I’m doing it pretty much for myself. In quite a lot of things, when you’re disabled, you have to accept help from people to do even the most mundane tasks. With climbing, it’s literally on me and there’s quite a lot of responsibility which is mine, and it’s quite refreshing to have that.”

Julia Clarke is a staff writer for Advnture.com and the author of the book Restorative Yoga for Beginners. She loves to explore mountains on foot, bike, skis and belay and then recover on the the yoga mat. Julia graduated with a degree in journalism in 2004 and spent eight years working as a radio presenter in Kansas City, Vermont, Boston and New York City before discovering the joys of the Rocky Mountains. She then detoured west to Colorado and enjoyed 11 years teaching yoga in Vail before returning to her hometown of Glasgow, Scotland in 2020 to focus on family and writing.