I’ve just discovered I’m a super salty sweater, and it explains everything about my running

A sweat test and a training session in a heat chamber with a Marathon des Sables winner reveals I need to rethink everything

“Are you a salty sweater?,” asks Emily Arrell from the Sports Science Team at Precision Hydration, as she attaches a couple of wires to my arm in preparation to giving me a sweat test.

I’m on my 53rd lap of the sun now, and I have never been asked that before. I’ve never even thought about it. Obviously I know some people perspire more than others, but I assumed the consistency of that sweat would be pretty similar for everyone. I was very wrong.

Humans are deceptively complex beasts – we’re different from one another in so many invisible ways, and the make-up of our sweat varies massively. And this has big consequences, especially when you put your body through extreme experiences such as running marathons, let alone ultra marathons through deserts.

Into the lab

I’m at the Precision Fuel and Hydration lab with Dave, a fellow journalist, and Pierre Meslet, a sponsored elite athlete who has twice completed in the infamous Marathon Des Sables (MDS), placing 9th overall in 2021 and 6th in 2023, when he was part of Team France, victors in the team category of the desert-crossing event.

Pierre has just returned from Costa Rica, where he won the Coastal Challenge, a gruelling multi-stage 157-mile / 252km ultra marathon that traverses tropical jungles, beaches and mountains. Suffice to say he knows a thing or two about running in extreme heat and humidity.

The test that Emily administers to the three of us sends an imperceptible electrical current through our bodies, triggering our autonomic nervous systems to produce sweat in one part of the arm, where a vial has been positioned to collect it. This sample is then tested for sodium content.

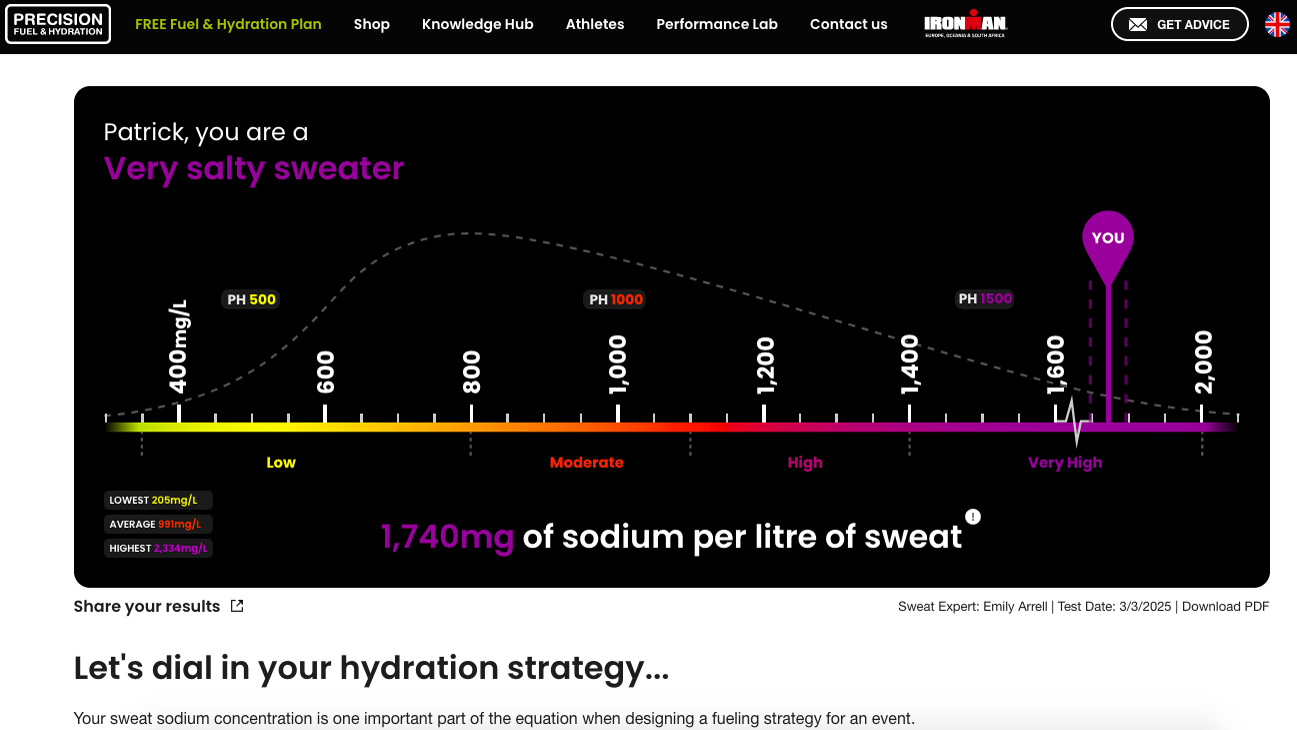

When results come back, I win – hands down. Dave’s levels are low and Pierre is in the mid range, while I score a sky-high result of 1740mg of sodium per litre of sweat – right at the very top of the scale. It turns out I am a one-man salt mine. In Roman times, when such substances were virtually a form of currency, I would have been considered a walking bank. And in case I’m in any doubt, an email arrives instantly on my phone announcing: “Patrick, you are a very salty sweater.” Great.

Advnture Newsletter

All the latest inspiration, tips and guides to help you plan your next Advnture!

There are, I learn, many clues that could have made me suspect this before getting a clinical sweat test done. Do I see white residue left on my running tops after a lengthy outing in warm conditions? Yep. Do I experience sweat stinging my eyes if I don’t use appropriate running headwear to soak it up? Also yes – I’m basically running half blind for most of the summer. Do I crave salty food after a big day on the trails? Feck yes! Doesn’t everyone? (No, apparently, at least not like I do.) So, having answered in the affirmative to all three of these questions, it shouldn’t have been such a surprise to learn that I am a very salty sweater.

But what does this mean? Emily and doctors Lindsey Hunt and Sam Shepherd (both PhD-qualified sports scientists) seem quite excited to have someone with such a high result, but I feel a bit alarmed. Am I about to keel over with a massive heart attack? Is my diet disastrously dangerous?

“No, don’t worry,” Lindsey reassures me. “While your results are certainly high, very high actually, it’s just the way you are. You were born like that. It’s nothing to do with lifestyle, and it’s not a problem, so long as you’re aware of it and adjust your intake of minerals during periods of high intensity exercise.”

Okay… but I definitely haven’t been managing it up to this point – I smash the occasional running gel when I’m doing longer events, and chow down on bars and other nutritional supplements if I think I need them, but that’s about as scientific as my approach gets.

“And do you ever suffer with cramp?” probes Lindsey? I definitely do, yes. Again, though – doesn’t everyone? Not if they’re aware of their salty sweat and properly prepared, it seems. “Lots of factors can contribute to you getting cramp,” says Sam. “But if you’re losing a lot of sodium, and not replacing it, that will certainly be a big factor.”

Sweating it out

I’m not the only one with crazy amounts of salt in my sweat here today. Andy Blow, founder of Precision Fuel & Hydration, has even higher levels than me. An accomplished triathlete in his day, with plenty of podium finishes to his name, Andy tells me that he really struggled in long-distance and hot triathlons, despite following a nutrition plan, and until he finally did a sweat test, he had no idea why.

“I discovered that I lose a very high amount of sodium in my sweat,” he explains. “And this, coupled with the lack of awareness of the importance of replacing sodium at the time, meant that I was a higher risk of issues like cramp and low blood sodium, caused by sweating out too much sodium, drinking too much plain fluid, or most commonly a combination of the two.”

Although the revelation came quite late in his own athletic career, Andy realised how transformative this information could have been to his results, and in 2011 he set up a company to help other runners, cyclists and triathletes improve their performance by tailoring their intake to the conditions they’re racing in.

Feeling the heat

There’s more to this process than simply getting your sweat tested to establish its composition. To properly prepare for an event, especially one in extreme conditions, you need to know almost exactly how much you are going to sweat in the prevailing heat, and then formulate a plan. Precision Fuel has a facility in Dorset where they run tests on athletes running on treadmills and cycling on static bikes in a specially designed heat chamber, so they can harvest precisely these stats in a scientific setting.

During an event such as the MDS, where temperatures regularly soar north of 50°C and even the front-end competitors are running for over five hours a day, managing your intake of electrolytes correctly can be matter of life and death. In such conditions you can’t possibly intake as much liquid as you’re losing through sweat, but even if you could, without replacing electrolytes (crucially sodium, one of the components of salt), you’d be at severe risk of experiencing hyponatremia (a potentially lethal condition caused by low blood sodium levels).

“At one point during the MDS, my urine was a browny red colour,” Pierre tells us. “It was scary, but I talked to the race doctors, and they said so long as it returned to normal, it was okay. And luckily it did.”

There was more than luck at play, though. Before heading to places Costa Rica and Morocco to compete in ultra events, Pierre spends weeks training in heat chambers to pre-acclimatise his body, and uses the stats that can only be gleaned from facilities such as this one to work out a nutrition plan tailored to the challenge he’s taking on.

“At MDS I was drinking water loaded with this stuff all the time,” he tells us, waving a tube of PH1500 electrolyte tablets around. “I would double dose my bottles before setting off, and each evening I just kept drinking the solution. I even used it in my morning porridge.”

Before putting our shorts and running shoes on, we’re instructed to weigh ourselves naked. Once in the heat chamber, where the average temperature is maintained at 38.9°C, with 34% relative humidity, we’re allowed to drink water (loaded with electrolytes) but everything we consume is strictly weighed. Pierre sets a cracking pace on one treadmill, running for a full hour, while Dave and I do 40 minutes each on the second machine, as Lindsey and Sam constantly monitor our heart rates and regularly make sure we’re comfortable. Within a couple of minutes I start to feel beads of sweat rolling down my back, and by the end of the session I’m fairly soaked.

A second weigh-in and some calculations reveal that I sweat (in those conditions) at a rate of 1.4L an hour, which – to my relief – is actually a bit below average. I’ve had quite enough of being special for one day, and if my sweat rate was high on top of my sweat being super salty, then I would really be up against it.

The leaderboard on the heat chamber wall reveals some people perspire at twice that rate, with the record standing at an impressive 3.2L per hour. Of course, those people might well have been running a lot faster than me – Pierre’s pace was much quicker than mine, and he was sweating at a rate of 1.88L per hour, even though he is obviously much fitter, and he still retains some residual acclimatisation from his Coast Rica escapade.

“Despite Pierre running 4km/h faster [than you] and for 20 minutes longer, his peak core temperature and yours were quite similar,” observes Lindsey. “This indicates just how more tolerant of the hot conditions Pierre is than most mortals.”

However, he continues: “Both yourself and Pierre still lost more fluid per hour than it's generally feasible to replace during prolonged exercise. Most individuals who are used to drinking high amounts of fluid may be able to tolerate up to 1L per hour, but generally beyond that rate of fluid ingestion it becomes reasonably challenging without substantial practice.

“The challenge that comes with a high sweat rate is that fluid and sodium losses can mount up quickly and, as Pierre said on the day, not adequately replacing those losses can be the difference between being peeing an uncomfortable hue of red during MDS or staying in contention at the front of the race. Luckily, focusing on appropriate hydration pre during and post-exercise, many of these risks can be mitigated.

“As you can see in the data from your heat session and your Sweat Test, both how much you sweat and how much sodium you lose in that sweat varies massively from individual to individual, which is why the world's best athletes spend so much time personalising their hydration strategies.”

The plan I walk away with, which is designed to see me safely through a marathon in regular conditions, is to take in 600ml of liquids per hour, with 1000mg of sodium per litre, plus 60g per hour of carbs. I’m not planning on entering the MDS just yet, but I do have a 20-mile multi-terrain event coming up that I have done over 10 times before, and I have always cramped towards the end. This time I’m going into it armed with the knowledge that I’m a super salty sweater, and I have a plan to follow – let’s see what difference it makes.

Author of Caving, Canyoning, Coasteering…, a recently released book about all kinds of outdoor adventures around Britain, Pat has spent 20 years pursuing stories involving boots, bikes, boats, beers and bruises. En route he’s canoed Canada’s Yukon River, climbed Mont Blanc and Kilimanjaro, skied and mountain biked through the Norwegian Alps, run an ultra across the roof of Mauritius, and set short-lived records for trail-running Australia’s highest peaks and New Zealand’s Great Walks. He’s authored walking guides to Devon and Dorset, and once wrote a whole book about Toilets for Lonely Planet. Follow Pat’s escapades on Strava here and Instagram here.