Mythbusting: does it really take longer to boil an egg at altitude?

Does it really take longer to boil an egg at altitude? What about to make a decent cup of tea or a lovely coffee? We’re here to provide the answer

Having crossed the spectacular Piuquenes Pass in the Andes, Charles Darwin had some trouble boiling his potatoes. It was the 1830s; the young Darwin was part of HMS Beagle’s famous second voyage and was studying the geology of South America. These were studies that, along with his observations of the native wildlife, would guide his thinking and later lead him to introduce the theory of evolution by natural selection, along with Alfred George Wallace.

But that’s another story. Let’s get back to those spuds. In his classic travelogue The Voyage of the Beagle, Darwin observed that “the elevation was probably not under 11,000 feet,” which is around 3,350 meters for those who prefer a bit of metric. “At the place where we slept water necessarily boiled, from the diminished pressure of the atmosphere, at a lower temperature than it does in a less lofty country… Hence the potatoes, after remaining for some hours in the boiling water, were nearly as hard as ever.”

Despite his best efforts, poor Charles just couldn’t get his potatoes to cook. He’d observed that water was boiling at a lower temperature than usual and that it was having a negative impact on his attempts to make dinner. He wasn't the first, or the last, person to recognise the effect of altitude on boiling temperatures and on cooking. So, what’s going on here? Our mountain loving former school head of science is here to break it down. You see, it all boils down to this…

Meet the expert

An avid backpacker, Alex enjoys firing up his camping stove in the mountains and settling down to an evening meal with the summits for company. Although most of his wild camping has taken place in the UK’s relatively diminutive mountains, he’s enjoyed numerous adventures in the European Alps and has first-hand experience of the effect altitude can have on cooking. As an Englishman, he also loves a cup of tea.

Today’s best deals

The myth

As observed by Darwin, water seems to boil at lower temperatures in “lofty” places – in other words, at altitude. This leads to difficulty cooking food, particularly where boiling water is concerned. Apparently, it takes longer to boil an egg at altitude, while some claim it’s nigh on impossible to make a decent cup of tea or a delicious mug of coffee. Let’s drill into the science to see just what’s going on.

The evidence

At higher elevations, air pressure decreases, which you’d expect as there’s less volume of air bearing down on any given point than there is at sea level. If your ears have ever popped on a flight, you’ll have experienced this change in pressure firsthand.

We all know that water evaporates when it’s heated, changing from a liquid into a gas. The amount of pressure on the surface of a body of water affects the rate of evaporation. The higher the pressure, the more difficult it is for water molecules to escape as vapor. Only when the vapor pressure caused by heating equals the atmospheric pressure will evaporation occur.

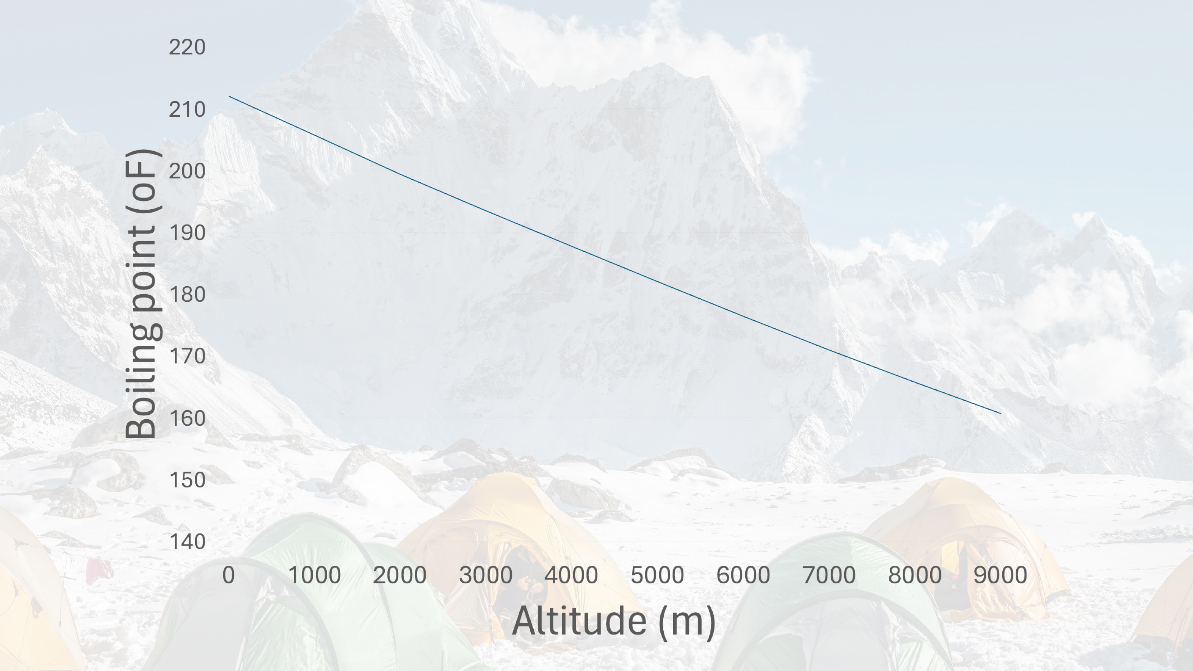

At sea level, the pressure is comparatively high, so it requires more energy to cause water to evaporate than at altitude, where the pressure is lower. Due to this, the boiling point at sea level is higher than at altitude. The table below shows the boiling temperature for various altitudes, with a few mountains thrown in for context.

Advnture Newsletter

All the latest inspiration, tips and guides to help you plan your next Advnture!

| Altitude (feet) | Altitude (meters) | Comparative mountain | Boiling point (°F) | Boiling point (°C) |

| 0 | 0 | Sea level (0 m) | 212.0 | 100 |

| 3,280 | 1,000 | Snowdon (1,085 m) | 205.7 | 96.5 |

| 6,560 | 2,000 | Mount Washington (1,917 m) | 199.4 | 93 |

| 9,840 | 3,000 | Triglav (2,864 m) | 193.5 | 89.7 |

| 13,120 | 4,000 | The Eiger (3,967 m) | 187.7 | 86.5 |

| 16,400 | 5,000 | Mont Blanc (4,809 m) | 182 | 83.3 |

| 19,690 | 6,000 | Denali (6,190 m) | 176.4 | 80.2 |

| 22,970 | 7,000 | Aconcagua (6,961 m) | 171 | 77.2 |

| 26,250 | 8,000 | Shishapangma (8,027 m) | 165.7 | 74.3 |

| 29,530 | 9,000 | Everest (8,849 m) | 160.7 | 71.5 |

The good news is that it’s still perfectly possible to cook an egg in this way, you’ll just have to increase the cooking time and wait until the white is firm. An egg will coagulate somewhere between 144°F and 149°F (62°C and 65°C), which you should be able to achieve at any altitude before water starts boiling, even the summit of Everest!

So, that’s eggs cracked, so to speak. But what about that all-important brew? Where does the Goldilocks zone lie in terms of bringing out the best in your tea leaves? Too hot and you’ll destroy the tannins that produce tea’s delicate flavour and lead to a bitter brew. Too cold and the tannins won’t dissolve, resulting in a tasteless tea. It’s thought that for the perfect black tea you should aim for between 195°F and 212°F (90°C and 100°C), while a green tea can be much colder, between 195°F and 212°F (65°C and 80°C).

Coffee lovers, who I count myself among, I haven’t forgotten you. Various sources suggest that the ideal water temperature for a lovely mug of joe is around 195°F and 205°F (90°C and 96°C), putting it in a similar range to black tea.

So, for both tea and coffee, this is good news for most flask-carrying hikers but bad news for high altitude mountaineers. Beyond 3,000 meters (10,000 ft), water won’t reach 195°F (90°C) before it starts to boil, making crafting the ideal brew difficult even with the best coffee maker around. Unless, that is, you’re a fan of green tea, in which case you should still be able to make a decent brew, even on the summit of Everest. I’d guess you’d probably have other priorities if you were up there though.

And Darwin’s potatoes? Various sources suggest potatoes need to be boiled at a high heat, slightly in excess of the 195°F (90°C) that he’d have been able to achieve near the Piuquenes Pass in the Andes.

Of course, there are other factors that also come into play that will have a bearing on boiling and cooking times, such as the stove’s flame being negatively affected by the wind, or the type of stove and the kind of fuel you’re using. White gas – a liquid, despite its name – is the fuel of choice for high-altitude expeditions, outperforming canister stoves.

Fact or fiction?

While water will reach its boiling point quicker at high altitude, it will take longer to cook an egg. This is because water boils at lower temperatures, so achieving a higher cooking heat is difficult. The good news is, there’s no need to worry, you just have to increase the cooking time to make a lovely poached or hard-boiled treat. This means you’ll have to increase the amount of fuel you’d otherwise take.

The perfect cup of tea or coffee becomes increasingly difficult to achieve the higher up you go and, as a result, it will take longer to make a decent brew. Beyond around 3,000 meters 10,000 (ft), water boils before the ideal temperature range for both coffee and black tea. As with cooking eggs, increasing the infusion time may help with flavor, but once you get really, really high, it’s going to be difficult to create the delicious brews we’re accustomed to at sea level.

Alex is a freelance adventure writer and mountain leader with an insatiable passion for the mountains. A Cumbrian born and bred, his native English Lake District has a special place in his heart, though he is at least equally happy in North Wales, the Scottish Highlands or the European Alps. Through his hiking, mountaineering, climbing and trail running adventures, Alex aims to inspire others to get outdoors. He's the former President of the London Mountaineering Club, is training to become a winter mountain leader, looking to finally finish bagging all the Wainwright fells of the Lake District and is always keen to head to the 4,000-meter peaks of the Alps. www.alexfoxfield.com